Ten useful basic lessons

1) There are acceptable and

unacceptable places to perform

2) Dogs don’t bite humans

3) Coming when called

4) Greeting guests politely

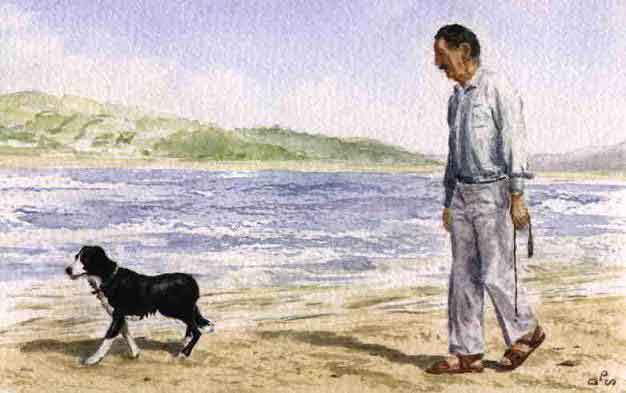

5) Walking nicely on the lead

6) Respecting passers-by, human and canine

7) Being sensible with traffic

8) Travelling safely in cars

9) Learning that some animals

are prey, others are not

10) Respecting other dogs in the household

Introduction: Who needs training, humans or dogs?

A lot of training advice focuses on the dog, but sometimes we need to train ourselves if we want to help our dogs to behave better. Firstly, training ourselves to develop routines helps a lot. Then we can get tasks done more easily, and our dogs know when important events like eating and walks will happen. This makes for a more relaxed relationship.

Routines are part of getting organized, with a weekly training plan geared towards long-term goals. Keeping a training diary can help a lot with recording progress, and identifying areas that need more work. Each dog is different, so it makes sense to be flexible, and gear a training plan to a particular dog, rather than try to rigidly impose a plan from a schedule of what an imaginary dog should be doing.

Secondly, it helps to train ourselves to anticipate potential problems, so we don’t put ourselves and our dogs into situations we aren’t ready to cope with. Many dogs are tempted to chase joggers, for example, so a long-term plan to tackle this has to be coupled with prevention until the dog is reliable. It’s safer to start with restrictions, like a short leash, and gradually give more freedom as the dog becomes more reliable. That’s much better than having to impose restrictions after an incident!

Thirdly, training ourselves to observe and understand canine body language is very important. It makes two-way communication possible. Dogs can tell us how relaxed they are from their body language. Their eyes and tails are in a more natural position when they’re relaxed, while their eyes may be wide open, or narrowed when they’re aroused. Happy, curious dogs tend to have their tails up, while worried dogs put their tails down. It’s well worth while spending time watching dogs together, just to get a feel for how they communicate with one another. That helps with understanding what they try to tell us.

Being able to understand what our dogs are saying means we can help them to behave better. A dog can say ‘I’m worried about that large dog approaching’, and we can answer with ‘OK, we’ll give it a wide berth’, or ‘What’s that strange object?’ and we can say ‘Let’s go see and check it out.’.

Fourthly, we need to train ourselves to be aware of what our body language is telling our dogs – they can read us better than we can read them. This means developing consistent gestures when we ask them to do something like get off the sofa. It also means having relaxed body language around people and objects we want our dogs to be relaxed with.

Lastly, we need to train ourselves to remember that dogs are learning from us all the time. Dogs are clever clogs, they’re constantly checking us out for clues as to whether there’s a chance of doing something interesting together. Most of what pet dogs learn is through everyday interactions with their owners, rather than in the few hours of formal training sessions, yet we aren’t always aware of what we’re teaching them. ‘What is my dog learning from this?’ is a very useful question.

What’s the point of training?

Training is about teaching your dog what he needs to know for life together to be enjoyable for both of you. What’s worth putting a lot of effort into depends on what he needs to know, and what he already knows. Coming when called is important for all dogs. Country dogs especially need to learn to respect livestock. City dogs need to cope with passers-by, their dogs, and traffic, and learn to walk nicely on the lead. Dogs in multi-dog households need to learn to get on with one another. There are ten suggested lessons at the end of this article. Your dog will already know some of the lessons, and you may want to add your own ideas. You're the trainer.

Training in the wider sense is about teaching coping skills, good habits and rules. Coping skills include being able to cross a busy road without being spooked by traffic noises. Good habits include sitting or standing nicely at the kerb to cross the road. Rules include greeting visitors politely, rather than jumping up at them.

Training is more than just commands, like 'sit'. You've maybe taught some commands, and have probably already taught your dog a lot more, both good and bad habits, sometimes without realizing it. For example, a dog that does a perfect sit in obedience classes may have learnt that it's OK to jump up and down like a lunatic before you open the front door. If you've let him do that, you've trained him it's OK. Try listing what your dog has learnt. List the good stuff as well as the bad, because it helps your morale, and you can build on your dog's strengths. Most dogs have both strengths and weaknesses. Dogs brought up with kids from puppyhood, for example, may be very tolerant and well-behaved with kids they know. That can help them learn to behave well with strange kids, even those who rush past them screaming, as kids sometimes do.

Remedial training

Quite often owners only start to think seriously about training when a pup has started to turn into an unruly dog. Then a thought may hit you on the lines of 'Oh dear, maybe I should have trained him a bit better when he was little'. This is especially true if it's your first dog, or your previous dogs have always been calmer and more biddable. Challenging dogs can be good teachers, you'll know better next time! In the meantime you may be tempted to switch from being indulgent to being stern and strict, and that could be confusing for your dog. It's possible to train a dog well and still give him or her lots of cuddles, so long as the timing is right, and you’re giving rewards (like cuddles) for good behaviour. Most dogs want to be entertained as much as possible. Dogs who are rewarded just for being cute are more likely to get pushy and demanding, so if your dog is a bit pushy, make him earn his rewards. You may also want to control access to toys, allowing the dog to play at your invitation, and putting the toy away when you've finished, rather than letting him carry it off as a trophy.

Obviously it'll confuse a dog if you suddenly get cross with him for doing things he's previously been allowed to do, and that confusion can undermine trust. But you can break bad habits you've let him get into, by calling him to you, or getting him to sit, by giving him a command that tells him to do something else. You can also put barriers up if you no longer want him on the furniture, or in the bedroom. Once he’s got out of a bad habit you’ve previously allowed, or if he starts doing something new you would rather he didn't, then you can spell out that it's not allowed. It can be very helpful for dogs to be told 'I don't want you to do that', it gives them information they need to know. 'Chsst' is a handy sound for getting a dog's attention and is much more effective than 'No' It can both convey owner displeasure, and get the dog's attention. Once he’s looking at you, you can tell him what you want him to do.

Trust me

Some dogs are naturally trusting, others are warier. Being predictable and consistent about rules helps make you trustworthy, as does being firm and gentle when you touch your dog. Two-way communication helps with building trust, checking out his body language to see how he feels, checking what your body language is telling your dog, and whether it fits with what you want him to do. Using consistent gestures and words to send him messages helps build trust, as does noting how he tries to tell you what he wants.

Scolding can undermine trust, especially if the dog has no idea why you’re angry. In general it’s better to call and leash a dog when he’s thinking of mischief, so you can praise the recall rather than scold for a misdeed. Sometimes, though, dogs do need to learn that some actions are dangerous, like stealing food. You can set up a booby trap so the dog doesn't realize you have anything to do with what happens, like arranging empty tin cans that fall down and clatter if he tries to get at something from the kitchen counter. Make sure that nothing in your trap is dangerous, and that it's just scary enough to do the job, not so scary that he becomes reluctant to come to you if you call from the kitchen.

It’s easy to understand that dogs and people distrust those who are unpredictably angry. It’s less easy to understand that sometimes doing nothing can make us untrustworthy. If your dog’s really spooked by something, telling you about it with body language or barking, and you’re not listening, then you become less reliable. Say your dog is barking at something outside. A quick check can reassure him that you’ve listened, it’s not a threat, and he can be quiet. Doing nothing may lead him to bark louder. Or say he’s on a walk and can’t work out whether an unfamiliar object ahead is dangerous. Give him time to check it out, and work out it’s safe for himself.

Helping a dog to feel safe and better able to cope makes you more trustworthy. Humans have our beds as safe places where we can relax. Respecting a dog’s bed as a safe place also helps him to relax, and to trust you. It’s only a safe place if family and visitors also respect it as a place for the dog to have peace and quiet, and enforcing this rule makes you more trustworthy.

Trust is about developing mutual respect and affection, rather than never disagreeing with your dog in case you upset him. It involves listening rather than just barking orders. It’s also about taking responsibility, being aware of what might be spooking your dog, and either dealing with it, or helping him to deal with it.

Listening to dogs

Dogs try to tell us what they want in all sorts of ways, such as looks, nudges or barks. Confident dogs ask us to do things with them several times a day. Sometimes it’s very clear what they want, like when they bring us a lead. Other times it’s less clear. We can train them to communicate better by answering with a ‘not now I’m busy’ signal’, or a ‘Yes, ok, let’s do it’, rather than just telling them to shut up. When they tell us what’s happening in their world, we can answer with ‘Thank you for telling me the rice was burning’, or ‘the dog that just passed by has gone now’, or ‘yes, there’s someone at the door, now sit in your basket and I’ll check it out.’ Answering means that dogs continue to communicate, and don’t feel they have to shout to get our attention. Obviously dogs will tell us stuff we already know, or stuff we don’t want to know. Even so, if we treat barking purely as ‘unwanted behaviour’ we may be able to get a dog to bark less in the long run, but we’re missing out on an opportunity to communicate.

Dogs also tell us about their feelings through their body language, like whether they’re confident or spooked, spoiling for a fight or friendly. A dog's body language can tell you, for example, that an approaching dog is one they really don't want to be close to, or that they really prefer not to be kissed, and are just being polite when they accept it. Kids can sometimes be very stressful for dogs, so need to be supervised. Checking out a dog’s body language in any interaction helps with anticipating and so preventing trouble.

Dogs tell us from their body language which activities calm them, and which make them excited. This means we can calm them down when they start to get overexcited, or arouse their interest in an activity we want to do together. Settling down for a cuddle and tidbits can help to relax a dog that has become overexcited through play, and is about to get bitey.

It’s very important to be aware of how touch affects your dog, and this varies from one dog to another. Generally, long, slow strokes tend to be relaxing. Some dogs are happy with kisses and ruffles to the top of the head, but dogs usually need to learn to accept hands coming from above them, and are more relaxed by hands to the side of their heads. Some dogs are reassured by touch when they are a little upset, but can interpret any touch as a threat when they are very aroused and upset. If in doubt, give the dog space to calm down, and let him come to you and ask to be touched.

Being able to read a dog is very important when you’re working out what the dog can cope with. You want to set your dog up for success, rather than put him in a situation where he reacts badly. If he’s very spooked by big dogs, he needs to get used to them from a distance. If he’s just a bit worried, walking him alongside a well-behaved big dog can help him learn to relax.

Dogs listening to us

Dogs, of course need to listen to us too! Teaching a dog to pay attention is easier with some dogs than others. Some dogs are wonderfully attentive, checking constantly to see what we want them to do. Others need reminding we’re there. There are times dogs simply don’t hear us, like if they are chasing prey, or are very upset, so if you want to your dog to listen, he needs to be receptive.

Using a long line for your first training sessions helps to remind your dog you’re there, and helps remind you to communicate clearly. Interacting with dogs on walks helps keep them focused on us, rather than amusing themselves. Giving them interesting tasks to do makes us interesting. It’s also worth telling the dog about approaching humans or dogs that you can see and they can’t, because your dog is prepared, and you’re a useful source of information.

Whistles are used in gundog and sheepdog work, and are very useful for communicating at a distance. Sheepdog whistling techniques are more complex, and most pet dog owners will find gundog techniques easier to use, while giving enough information to the dog for most needs. There are, for example, whistle calls for recall, for stop, and for turning in different directions.

Dogs close to us can pick up a lot of information from watching our faces, and even our eyes. Some dogs are wary of looking people in the eye, especially adult dogs which have previously lived in kennels. If that’s the case, you can reward for eye contact, and raise interesting objects, like food and throw toys, to your face, so the dog looks at your face and the object. Once a dog looks at your eyes, you can also encourage the dog to follow your gaze by moving your body and pointing towards an object as you look at it saying ‘look at that’, then by moving your head and shoulders and looking, then just your head, until you can just look, saying ‘look at that’ and the dog looks in the same direction.

You can also train a dog to touch your left hand by moving it, then rewarding him with food from your right hand when he touches it out of curiosity. Once he touches your hand when you ask, you can use this to teach heelwork. Similarly, you can teach a dog to touch a post-it, or other adhesive object, through rewards, then build up distance between you and the post-it, so send the dog to different locations.

When dogs have learnt to focus on us, it’s also possible to teach them to do something, like standing on a table by doing it ourselves, then asking them to copy us. There is a book on this innovative technique in Further Reading at the end.

Using food rewards

Many books and trainers recommend tidbits for rewards. Tidbits are very useful both as rewards and as lures, to attract and keep your dog's interest. They should be small, and smelly tidbits are especially attractive. Try out different types of tidbits - dogs vary in terms of how they respond to them. Dogs that aren't very food-oriented may need smellier tidbits, while food-oriented dogs may work better with more boring tidbits, (otherwise you may find that they focus on the tidbit rather than what you want them to do). The tidbits have to be small so that they can be eaten fast. You can use them on your first walks with a pup or new dog, to reward the dog for coming back when you call. Tidbits are of course food, so bear in mind how much your dog has already eaten as tidbits when you prepare meals, or you may get a very fat dog! Meals are an important ritual in the day, when a dog can relax and just eat, so save some food for mealtimes rather than trying to feed everything as rewards.

Tidbits can also help with relaxing dogs that are unconfident about slightly scary surroundings. They’re more effective if you ask the dog to do something like lie down, and then reward for doing what you ask. The interaction with you helps distract from the surroundings. Very spooked dogs who initially ignore tidbits may respond better if you offer them something interesting to do with you, and then give them a tidbit for doing as you ask.

Tidbits aren’t the only way to reward dogs, and often they will be rejected. If a dog wants to retrieve, a ball is often more interesting than food, so throwing the ball can be a better reward for a sit than giving a tidbit. Sometimes though, dogs can get too wound up with fun activities like retrieving or tugging. Ending the game, and switching to tidbits as rewards for sitting can help calm them down.

Manners and skills training can mesh together

A lot of basic training is to do with teaching self control and good manners with humans and other dogs. It’s socialization, or learning social rules, as well as learning to cope with strange noises and sights from washing machines and other inanimate objects. 'Manners training' or teaching dogs to behave well around people and other animals, is often seen as different from 'skills training', or teaching dogs to do useful activities. The first usually stresses not doing things, while the second is more about doing things. Professional trainers often divide instruction into obedience, which helps with learning self-control in social situations, and skills, like agility. Dogs tend to prefer skills classes where they do things, rather than obedience classes where they put most of their effort into not doing things. However, the two types of training do in fact mesh very nicely. A very effective way of teaching the self control needed for good manners is to combine 'being still' or 'giving something up' commands with activities which dogs generally find enjoyable. This helps to motivate your dog so makes him more likely to obey. For example, if sitting nicely brings a reward, such as a ball being thrown, the 'sit' command is strengthened. You can also lay a scent trail with a sausage, and reward a nice sit with an ‘OK’, then a ‘Sniff’ command. Following a delicious smell to some tasty sausage is a reward for sitting. You could just scatter food and let your dog forage on the ‘OK’. Combining interesting activities with obedience makes training more fun for both of you, and it gives you more control when you’re teaching active skills.

Teaching a very basic retrieve can be fun. One way is to encourage the dog to bring objects back by throwing them, giving lots of praise for his bringing them back, then throwing them again. You can arm yourself with a lot of throw objects so that the dog naturally drops one to retrieve the next. Say 'fetch' when the dog goes to fetch an object, 'drop' when the dog drops the object, or ´give’ when he gives you the object, so he learns what the words mean. 'Drop' and ‘give’ are much easier to teach if they mean the game carries on.

Once your dog has grasped the basics, you can bring a 'sit' into the game. A dog that likes retrieving quickly learns that sitting nicely means that you to throw the object for them, whereas if they leap up and try to grab it, you won't throw it. If you always make them sit, they'll eventually sit automatically. With very keen retrievers, you need a super-reliable sit, because they can damage hands by trying to grab the throw object.

Keen retrievers can quickly learn to retrieve after a sit coupled with a stay. You can gently restrain the sitting dog and say 'stay' when you throw the object, then let go and say 'fetch', to teach him only to go after an object when you give permission. After a while when he feels ready, you can try throwing the object with a 'stay' command without restraining him, going back to the gentle restraint if he doesn't stay.

You can also combine tug games, which dogs often love, with a retrieve, so reinforcing 'drop' or ‘give’ (try a higher value object, or a tidbit to get the dog to drop the tug at first). When the dog has let go, throw the tug as a reward. The dog should then bring back the tug for more fun. Having a dog bring things to you on command can be very handy, especially if the dog can reach them and you can´t.

Dogs vary a lot, and what's a reward for one dog may not interest another, so learn from your dog what he likes doing, and use this as a reward. There are books on training games for dogs which explain a variety of games that you can try out, to find those that most interest your dog. Generally dogs like doing what they were designed to do, for example gun dogs designed to bring back birds tend to be good at retrieving. You may not have sheep for border collies, but they’re very versatile, and can excel at retrieving, agility and scent work.

Skills training is very useful in many ways. It tends to involve off-leash work at a distance, which gives you more confidence on walks. It provides motivation, builds up trust and helps you to communicate with your dog. It is also worthwhile because it's enjoyable for you. It's a great feeling of achievement to see what your dog is capable of, and to know that you’ve helped to train him, you've given him the opportunity to show what he can do.

Enlisting allies

Allies can be very helpful. They can help boost your morale, and ensure the dog gets the same messages from people close to him. If you live with other humans, working together helps enormously. Can you all agree about rules, like whether or not the dog is allowed to beg while humans eat? It's much easier to train a dog if everyone agrees both on the rules, and on the words you use to enforce them, like 'off' for getting off furniture.

A good trainer can help you with particular training problems, as well as teaching you how to teach commands. If you think your dog is a risk to you or other people, you really do need help from a trainer or a behaviourist who has a good track record in solving the problems you’re faced with. When a dog suddenly starts behaving badly, this may well be a medical problem, rather than a training problem, so a friendly vet is another useful ally. Experienced owners you meet on dog walks often love to pass on tips, some of which can make life much easier for you.

Dogs learn from one another, so it's also very useful to have canine allies. Sit-stays, for example, are much easier to teach if you already own a well-trained dog who a newcomer can watch. Some dogs are happy to teach newcomers, pups or otherwise. Other dogs may find the role a bit much, and may need protection if they find a newcomer too pushy, or they may not be well-behaved enough to set a good example, or your new dog may be an only dog. Even so, you can look for canine allies elsewhere, who can set a good example for your dog. Fellow dog walkers are often happy to have company, especially if your new dog is a cute youngster.

Walks and other activities

A long daily walk brings huge training benefits. It's an opportunity to get to know each other, explore and interpret the world to each other, and when humans can give guidance on issues they understand better than dogs, like that traffic is usually quite safe if you keep on the pavement next to your owner. When you get home, your dog is likely to sleep contentedly, and you can nod off. Morning walks are also important if the dog has to be left alone. The bed may be nice and cosy, and outside cold and frosty, but five minutes into the walk you are looking at your dog's joy at being alive, and glad you made the effort. Walks mean you are doing something together. Walks can also allow your dog to run off steam, if you can find a place where he can be safely off leash.

Walks help combat 'cabin fever' by providing novel smells and sounds - even a short walk round the block can calm your dog and help you enjoy each other's company more, but not everyone lives somewhere where it’s easy to walk dogs. Local parks may be too crowded with badly-behaved dogs, though this often depends on the time of day. There are activities you can do at home. Ball games in the garden can help to relax your dog, and help with training, if you incorporate sits, stays and giving up the ball nicely into the games. Indoor activities, like sniffing games, can also calm dogs. Local dog clubs may offer classes teaching agility, or other activities.

Teaching basic commands

Training, then, isn’t just about teaching commands, which are words or phrases with gestures that tell your dog what you want. Some people call them ‘cues’, feeling that ‘command’ sounds a bit too military. Whatever you call them, they are useful. They make it easier for your dog to understand you. ‘What are you doing on the sofa with those muddy paws?’ isn’t as informative as a simple ‘Off’, for example. Commands help with teaching rules, for example a word or phrase that means 'please wee here' helps your dog know where it's OK to wee. 'Drop' is a useful word to teach a dog to drop objects from its mouth, or ‘give’ if you want the dog to give you the object without dropping it. 'Leave' is a useful for telling a dog not to touch the chicken bone he’s spotted in the street. 'Sit' and 'lie down' are very useful in a range of situations, especially for greeting visitors nicely. You can use 'sit' if you feel your dog is about to jump up on a guest, for example. 'Go to basket' is also handy when visitors come. 'Stay' is useful both when you leave your dog and don't want him to move until you say so, or if you’re at a distance, and want him to keep still. ‘Wait’ is useful when you don’t want your dog to jump out of a car into traffic, but wait until it’s safe. Teaching ‘off’ means you can get your dog off the sofa or bed when you need to use them, while ‘down’ tells a dog that’s jumping up to get back on all four paws.

Teaching commands helps to keep dogs safe, and when they can be relied on to do what you ask, they can enjoy more freedom. The one essential command is recall. It can both get your dog out of trouble, and prevent him from causing trouble. You might think 'sit' essential, but many country dogs live well-behaved lives without ever sitting on command, they tend to lie down if told to stay. Work out what commands are most useful for you, then teach and use them.

Training classes can help with learning how to teach commands, and how to fit your body language with what you’re saying. You may be taught specific words in a training class, but you can use any word for a command, so long as you're consistent. You can also invent commands that help you. Some people use 'downstairs'. 'All gone' is handy for 'stop hassling me for a tidbit/ball', and you can show your empty hands. (Don't give in after you've said this, or you train the dog that hassling you can be effective!)

Commands are both about telling your dog what to do, and giving information. You do need a 'release' word if commands that mean being still, like 'sit' and 'stay', are to be effective, otherwise your dog doesn't know how long he is meant to sit or stay. An active command like recall obviously releases a dog from a 'being still' command, otherwise you can use 'OK now' or another expression to tell the dog there's no longer any need to keep still. Likewise if you use an 'I don't want you to do that' expression, like 'chsst', it helps to follow it with 'this is what I want you to do', which allows you to praise, rather than having to scold.

There are many books on teaching commands, and many methods today use tidbits. For example, to teach 'sit', you can place the tidbit in front of the dog's nose and move it slightly back and up, so he has to sit to follow it, while you say 'sit'. Then he gets the tidbit. He should learn fast that sitting when you say sit brings a reward. Once he has sat, it's easier to get him to lie down. Again you need the tidbit in front of his nose, then take it to down to his feet and along the ground in front of him, gently pressing down his rear so it doesn't stick up as his head goes down, following the tidbit. Say 'lie down' as you do this. Eventually he'll lie down on command, and won't need to sit first. Keep the 'sit' and 'lie down' commands separate, because it's confusing for a dog to be told to 'sit down' - he doesn't know whether to 'sit' or 'lie down'.

Tidbits can be useful for teaching new commands, but should eventually be phased out once dogs know the commands. Owners sometimes rely too much on tidbits. That's why some people never use them at all, and rely on other rewards, like praise or cuddles, and other lures, like a ball or a toy.

Some trainers use ‘hands on’ methods, guiding a dog into a position such as ‘sit’ or ‘stand’, using their hands, being careful to be gentle and firm, rather than forcing an unwilling dog. When this is done well, it has the advantage of building up trust. It takes more skill to do this than to use 'hands off' methods, so ‘hands off’ techniques tend to be more common. However, if you don't touch a dog when you teach commands, you still need 'hands on' exercises to teach your dog to accept being touched. If a trainer uses ‘hands off’ methods for commands, check that the trainer can also teach you how to get your dog to feel relaxed about being handled, groomed, having nails trimmed, and being examined by the vet.